Charles A. Minnie, the colored youth appointed to a West Point cadetship from the fifth senatorial district, was born in Lansingburgh.

“All Sorts.” Albany Morning Express. August 24, 1877: 1 col 3.

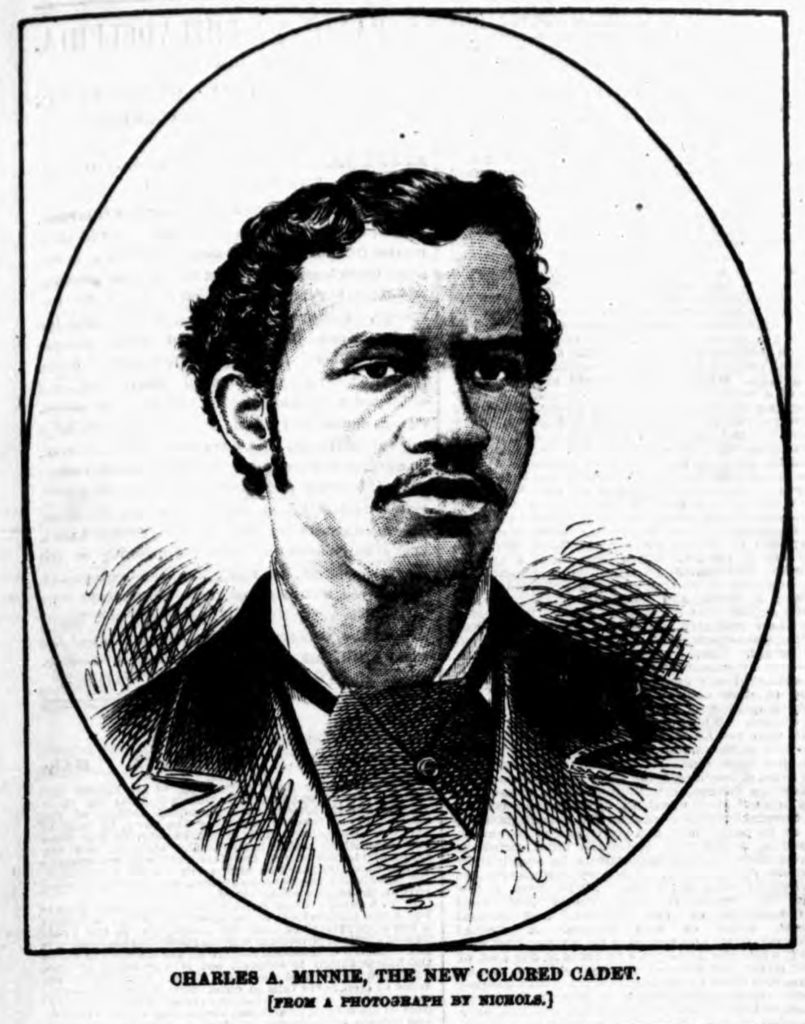

CHARLES A. MINNIE is the next colored boy whom the cadets at West Point are to ignore and maltreat, unless indeed by this time they have learned better manners. Young MINNIE has been selected to represent the first congressional district of New York city. He is eighteen years of age, and is credited with being bright and intelligent. His father was a Spanish mulatto and a blacksmith by trade. Young MINNIE was brought up in the Colored Orphan Asylum, and was adopted from that institution by Mr. WEBSTER, janitor of the Leather Manufacturers’ Bank. He attended the First District Grammar School in Greenwich Street, where he graduated last year at the head of his class. Since then he had been at Newport engaged as a waiter at the Ocean House. He returned about a week ago to compete for the cadetship. He is a good-looking boy, over five feet tall, substantially built, and with straight black hair, looking more like a Spaniard than a negro. We trust he may pursue such a course at West Point as to redound to his own credit and those whom he represents.

Lockport Daily Journal. August 24, 1877: 1 col 1.

Charles A. Minnie’s father seems to have died in 1864 or 1865:

Minnie, Charles, blacksmith, house Hoosick near Pitt, Lans.

Troy Directory for the Year 1864 Including Lansingburgh, West Troy & Green Island. Troy, NY: Young & Benson, 1864. 74.

Minnie, Charles Mrs. house Pitt st. alley n. North, Lans.

Troy Directory for the Year 1865 Including Lansingburgh, West Troy & Green Island. Troy, NY: Young & Benson, 1865. 76.

One more colored cadet has entered the classic precincts of West Point in the person of a lad called Charles A. Minnie, whose history is in some respects unique. He has won his position in a public competition incited by a democratic Congressman in one of the strongest democratic wards of New York city, and has apparently won it fairly by force of being the best educated lad in his district. The competition was thrown open to all scholars, public or private, and young Minnie carried the prize away by virtue of accuracy and proficiency in the ordinary branches of an English education, answering 99 per cent. of all questions asked. Another item of interest in his story is that the local democratic chief, John Morrissey, has sent the young fellow fifty dollars to buy his outfit, showing his hearty recognition of the perseverance implied in such a victory. We shall watch with much interest the future of this young man, not on account of his color, but his evidently exceptional talent, which owes nothing to favoritism.

Army and Navy Journal. September 1, 1877. 54.

—Charles Minnie the colored boy recently appointed to West Point by Congressman Muller of New York, was a boot black and sold THE DAILY SENTINEL here in the summer of 1874, his mother being the cook in Mrs. Sampson’s boarding home on Matilda street. His stand was just at the foot of the stairs in front of THE SENTINEL OFFICE. He was a wide awake and sharp boy, always attentive to his business, and will no doubt make a good army officer in time.

Saratoga Sentinel. September 6, 1877: 2 col 3.

“Charles A. Minnie the New Colored Cadet (from a photograph by Nichols.)” New York Daily Graphic. August 25, 1877: 381. (Cropped illustration from scan by fultonhistory.com)

—Charles A. Minnie, colored, recently appointed a Cadet at West Point, from one of the districts of New York city, has successfully passed all examinations and been regularly admitted as a Cadet. Thirty-eight other applicants out of sixty-five that were examined, were admitted.

Weekly Alta California [San Francisco]. September 15, 1877: 1 col 1.

HIS RETURN TO THIS CITY—WHAT HE SAYS ABOUT THE DAILY LIFE OF A COLORED CADET AT WEST POINT—HIS INTENTION OF JOINING THE CITY COLLEGE AND STUDYING LAW.

Colored Cadet Minnie, the graduate of Grammar School No. 29, in Greenwich-street, who last year passed the competitive examination for the West Point cadetship offered by Congressman Muller, of the Fifth District, has returned to this City, having failed to pass the January examination for advancement. Minnie is an intelligent, well-built, and rather good-looking young fellow, a slight dusky hue of his complexion being the only thing that would suggest that he was not of the white race. He said to a TIMES reporter yesterday that he felt confidence that he could have passed in mathematics, the study in which he failed, had he made any effort to prepare himself for the examination. He had neglected the study, however, being fairly discouraged with the uninviting prospect before him if he remained at the academy. He would have resigned long ago had not his fellow-students of his own race prevailed upon him at the time to abandon his resolution to leave. The treatment to which colored students were subjected, he said, was enough to sicken the heart and drown the ambition of any one whose feelings were at all sensitive. If, like [Henry Ossian] Flipper, the colored graduate, he had been born in the South, and had been used to hardship and ill-treatment, he might have smothered his pain and indignation, and remained to complete the course; but, born and brought us, as he was, in the North, and accustomed to kind treatment and social recognition, he was unable to bear the unprovoked insults that were offered him daily. In the public school in this City from which he had graduated he had associated with his school-fellows freely and as an equal, but in the academy, from the very moment he entered he was “cut dead,” and subjected constantly to a galling ostracism. Of the 300 white cadets in the institution there were but three or four that would speak to a colored student outside of official communication. The others never opened their lips to one except to curse or revile him. Even when the few to whom he alluded as being willing to address a colored student, were seen by their fellows in conversation with a colored cadet, they were remonstrated with, and every precaution taken to prevent their repeating the offense. The only relief from this social persecution was the considerate and gentlemanly treatment of the Professors and officers, who, Minnie said, allowed no distinction of race or color to alter their bearing toward any student. But notwithstanding that teachers and officers were thus invariably kind to him, he could not bear the grievous annoyances that surrounded him on all sides, and so, while he ostensibly yielded to the importunities of his friends to abandon his resolution to resign, he nevertheless made up his mind to let his cadetship go by default.

In speaking of his future intentions, young Minnie was more hopeful. He had been to see President Webb, of the City College, on several occasions since his return from the academy, to ascertain if he could not join the class of which he would now have been a member had he not happened to be successful in competing for a cadetship. He had passed the examination for admission last year, but President Webb, while expressing his willingness to admit him at the present time, had told him that it might be better for him to wait until the Fall, as he could then start fresh with a new class, and not have to undertake the task of catching up with the present class. President Webb had told him, however, that if he thought he could catch up, he might go to the college to-day, and books would be issued to him. He had not yet, he said, quite made up his mind whether to begin now or to wait until Fall, as Mr. Webb had suggested. He felt sure, however, that when he did enter the college he would not enter to be subjected to the same unjust and unkind treatment he had experienced at West Point. His studies there, he said, would be preliminary to a study of law, he being anxious to become a lawyer ultimately if he could. In concluding his story, Minnie inquired anxiously as to the health of Senator Morrissey, who, he said, had, although a perfect stranger, most generously furnished him money with which to procure a cadet outfit.

New York Times. January 26, 1878.

Charles A. Minnie, the colored Ex-West Point cadet, has recently been appointed a salesman in Browning’s clothing house in Philadelphia, which is one of the largest business establishments in Pennsylvania. The appointment was made to catch the colored trade, and as a business venture has been highly successful. If the merchants of Washington who desire the colored trade would appoint colored salesmen and women they would soon see how much they would profit by it. And if any of them want to be satisfied on that point let them call on Mr. Page, the grocer, on 13th and F street, who has a colored salesman.—Washington Bee.

Arkansas Weekly Mansion [Little Rock]. December 15, 1883: 1 col 6.

We are sorry to learn that Mr. Charles A. Minnie has been dismissed from his position as salesman; the reason given was the lack of support from the colored citizens.

State Journal [Harrisburg, PA]. December 22, 1883: 1 col 3.

Late in 1883, an ebullient young man, Charles A. Minnie, began a weekly contribution to the New York Globe. Like his counterparts in Boston and New Orleans, he describes a richly patterned social life, in which his fellow Philadelphians do dramatic readings and hold poetry or song contests at private parties. The churches put on plays and run benefit “star concerts” at the Academy of Music. He himelf goes to formal balls, catered weddings, and bachelor dinners. And then, to open his letter of November 17, he takes “great pleasure in informing the citizens of Philadelphia and vicinity of his appointment as salesman in Browning’s Clothing Store, Ninth and Chestnut.”

Minnie is exultant, even obsessed, and his next several letters amount to a kind of sermon on the Horatio Alger virtues. “We believe that if a number of our young men were to acquire a thorough business education they would find no difficulty in gaining admission into many of the mercantile houses of this city.” He himself won the job on only the second try. Others are also making it in the white world: “Kate Carter is an example of what a little energy will do. She is employed as a clerk at Frank Siddall’s office and in full view of the entire community.” There are other similar examples: engravers, bricklayers, messengers, and clerks. His own work goes well, his co-workers are friendly, and “the moral is plain: Young Men, Get Trades!”

The week before Christmas, Minnie is fired. The weather has been warm, sales have been slow, and “his people”—the account is written in the third person—are even slower to come by in the expected numbers. He protests that four weeks is hardly enough in which to show his stuff: the protest is in vain. A couple weeks later his byline disappears from the Globe.

This painful story is unusual only in that Minnie was given the illusion of opportunity; it was his friend, Kate Carter, who had a truly exceptional position. As late as 1900 only one percent of the city’s black labor force had been able to win jobs as clerks or salespeople, and the overwhelming majority of them worked for the government or for black employers. This Philadelphia story was only one chapter in the annals of a nearly universal discrimination. The telephone, typewriter, and department store together created an enormous new pool of jobs that had never existed before, but everywhere Afro-Americans were excluded from them.

Lane, Roger. Roots of Violence in Black Philadelphia 1860-1900. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1986. 36-37.

On the 1910 US Federal Census he was living in Philadelphia, employed as a clerk in the Post Office. On the 1915 NYS Census he was living in New York City, employed as a tea & coffee salesman. On the 1925 NYS Census, he was living in New York City, employed as a waiter, living in the household of Christine Manlove. On February 18, 1927 Charles A. Minnie married Christine Manlove in New York City. On the 1930 US Federal Census he was living in New York City, employed as a messenger of a printing house.

Christine Manlove Minnie died in Manhattan on January 12, 1936. Charles Minnie died in Manhattan February 4, 1938.